“Where Ends Meet, Five Miles From Hunts Point: Selling Fruits and Vegetables in the Global ‘Last Mile’ of East Harlem, NYC.”

What is the role of street vendors, independent grocers, and corner stores in the social process of food systems in global cities?

This is a question I worked to answer as a research assistant to Dr. Krishnendu Ray, as a contribution to a larger comparative project examining street food in global cities. This research began as a graduate internship (MS program Applied Social Research, CUNY, Hunter College) in the Spring of 2022 and is ongoing.

“Where Ends Meet, Five Miles From Hunts Point: Selling Fruits and Vegetables in the Global ‘Last Mile’ of East Harlem, NYC” focuses on a labor process organization across the logistical distance between fresh fruit and vegetable street vendors and independent markets in East Harlem and wholesale operations in the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center in the South Bronx, the world’s largest food hub.

Scroll to read field notes from one of the cases in this study and an image gallery taken in 2022 as part of my observation during over 40 miles of walking the street grids of East Harlem to understand the social process of exchange and transformation in the work of vendors and food workers who sell fruit and vegetables in NYC.

Check back for updates.

WORK ACROSS SPACE, AND IN TIME, AT YOON MARKET

Field Notes, March 2021:

Out front of Yoon Market, a small grocery store selling mostly fruits and vegetables in East Harlem, two men work to the sounds of a small, tinny-sounding, battery operated radio playing a global spanish-language mix of bachata, pop, salsa, reggaeton on 97.9 “La Mega” as they stock the street-facing displays outside on the avenue. They pluck out bad fruit, bring order to the piles, rearranging what has been picked over, stacking bins with “specials”: $1.00, $2.00, “2 for 3”, “3 for 2”, bundles of garlic in nets, duos of red and yellow peppers, trios of citrus or apples shrink wrapped to foam trays, bags of mixed salad greens, loose mangos, and packages of pre-shucked corn on the cob. Standing over these displays, the radio mixes with the small talk of workers and people shopping, the doppler effect of bass from car stereos pitch-bending down the block, voices from the sidewalk, street traffic, and the signal and air rushing out from suspensions of the MTA city buses dropping to the curb as doors opening onto the street in eight minute intervals.

These displays form two aisles that lead into the market, each bordered by stacks of crates, two high, one on top of the other with a third on top, facing up, open to eyes on the street. The store smells of alliums and earth, the salty funk of bacalao, the florals of herbs, and dried spices. Outside on the street and inside you can find pineapples, bananas and tropical fruits from far away places, alongside vegetables grown in temperate climates, some from the other side of the equator. All of which was brought here from Hunts Point, by van, one morning, this week by Harry Yoon, whose family has owned the single-story building and the market inside since 1978.

Harry took over from his aunt and uncle five years ago, he tells me, with all the seasonings of his very particular working-class, Korean-American, New York accent “my father used to run this place, then my aunts and uncles. Now me.” Before that, he worked for 20 years in the other, more “upscale” (he tells me) market the Yoon family run in Westchester County, north of the city. His knowledge of the history of this place is the memories of a child, or what he was told (and, of course, what he feels like sharing with me when we talk). When Harry’s parents, immigrants from Korea, bought the space it was already a produce market, one of many stores just like it; he tells me that when his parents ran the store you could follow the avenue up and down in both directions and find “green grocers” like this one every two to three blocks.

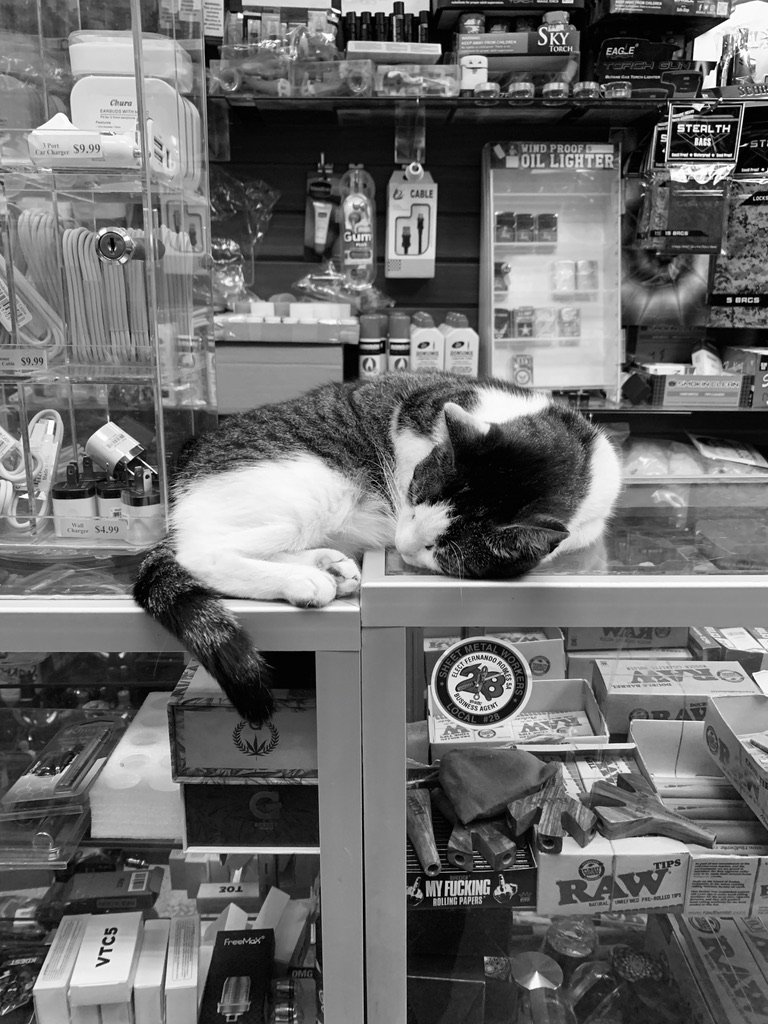

The store is sandwiched between a 5-story walkup tenement typical of the neighborhood and a hulking gray building with boarded and painted-over windows up above street level, and a ground level storefront that was once a pharmacy, then went unoccupied for years before a dollar store (where only “shelf stable” food is for sale) opened in 2021. The store on the corner buys and sells gold, it's the type of place where you can get a necklace engraved with the name of your love. Within a three block radius from this market, there are 12 street vendors selling foods at different times during the day, including: tamales in the AM, tacos sold from a minivan around noon, fresh juice and cut fruit in the afternoons, all night, there are other options: a cart selling jerk chicken, a stand selling quesadillas (and more), not to mention multiple restaurants, selling food from burgers to smoothies to cuchifritos.

Yoon Market is open seven days a week. Harry Yoon works 362 days a year, taking off Christmas, New Years, and the Puerto Rican Festival (“it’s not worth it to be open, no one buys, and everyone wants to use the bathroom”). On Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays (and sometimes Wednesdays “if we need it”) Harry goes to the Hunts Point Terminal Market to shop for the store. On days he goes to Hunts Point, he gets up at 4AM to drive over the George Washington Bridge to the South Bronx from New Jersey, where he lives with his family. He leaves when the store closes at 8PM, except Sundays when it closes at 6. Once or twice a month he leaves an hour or two early while someone else closes up shop.

Five people work at Yoon Market besides Harry. One worker, the only other Korean-American besides Harry, and the only woman, works the counter in the afternoons. All the other workers are from South or Central America; they speak Spanish amongst themselves and with customers. One opens the store everyday and works the counter before Harry arrives in the late AM, and then shifts to inventory and processing in the back room, where there is a walk-in refrigerator, and metal shelving that holds cases of produce ripening at ambient (room) temperature. Two workers rotate their time between the displays up front and the table at the back of the store, where cases are broken down into bags, nets, bundles, trays, and “specials” behind displays of dried sides of salted fish, seven or eight bins of tropical root vegetables, onions and other alliums, and different chili peppers. The last worker drives the van and pushes a hand truck on a five mile loop between Hunts Point and East Harlem.

At the counter, two steps up from the floor, in front of a wall of teas, herbs, candies, and ‘natural remedies,’ business is conducted primarily in English, although, in observing exchanges over time, it is clear that everyone who works here understands enough spanish to understand and respond to most questions, if in ‘spanglish’ (and sometimes with translation assistance from spanish-speaking workers). The math, of course, is fixed, in US currency: payments are accepted in cash, credit, or EBT (electronic benefit transfer, aka ‘food stamps’).

Compared to when his parents ran the store, Harry tells me, the landscape of fruits and vegetable vendors has changed. By the 1970s “La Marqueta,” the multi-vendor, retail market under the Metro-North elevated train tracks, had already closed. There are fewer small produce stores, more street vendors, and more supermarkets. However, he assures me that they, too, get their produce from Hunts Point, “everyone does. Even if they don’t say it… supermarkets get it from a distributor, but where do they get it from? Street vendors out here, same story.”

A few blocks away, in front of a “bank” on the corner—really a room, with 90 degrees of windows running parallel to where the street and the avenue connect, three ATMS, some metal, a card reader for entry, no tellers and no workers—there is an informal, mobile fruit and vegetable vending operation that specializes in Central American and Mexican produce. Two to three people work from a folding table, selling fruits and vegetables out of heavyweight cardboard cases from wholesalers, a few coolers, and three folding grocery carts secured to the table by bungee cords. One afternoon in May they had tropical fruits, like nance, mamey, and maracuyá, a selection of dried chilis, fresh green chilies, along with snacks, including chicharrones de harina/puffed wheat snacks, cacahuates/maní/peanuts. Other vendors also work this corner, selling tamales or gelatinas. All day, delivery workers pull up, lean their e-bikes on the frame of the light post to shop and eat, people passing by from the train pick up ingredients on the way home, or buy snacks as they head out.

Walk a few blocks in the other direction, there is a team selling produce on the streets, operating legally, with a “Green Cart” permit from the city out of a decommissioned “Access-A-Ride” vehicle (a small bus typically used for public transit for people with disabilities or mobility issues). During the day, the operation extends out into the street via a tent, folding table, and crates on a riser; at night, it all folds, rolls, and stacks away inside the bus, in what is, surely, a permanent parking space on the street. Over time, the architecture of this market has expanded, with new canvas tents, stainless steel bins, and another used van pulled up to the curb. The bodega halfway up that block does the same thing, except their street-facing storefront displays are brought back indoors at night when the metal shutter, painted with a mural depicting Mexican folk heroes, is pulled down over the store windows.

For Harry, street vendors “sell for the same prices as me, with no overhead.” Responding to a question about him owning the building, he counters that “he,” personifying the business, has to pay “electricity, taxes, garbage.” The Yoon market has a walk-in refrigerator, plus half a wall of glass-door deli fridges, running 24 hours. “For them it's all cash,” he continues, meaning they have no reporting, and therefore tax, requirements. He suggests that vendors use the garbage cans on the corner, as opposed to private businesses which, by law, must contract garbage removal services. It almost sounds simple how he tells it, “they pay for the permit and set up shop.” Of course Harry is inside, if in the weather when the gates are up and the front doors are open, he doesn’t face violence (from the NYPD which is notorious for harassing street vendors, for example), the full force of the elements, or have to find a bathroom. That said, every morning (minus three, yearly) he is just arriving around 11AM, in any weather, taking one last pull from a cigarette under the awning before he walks in for a workday that continues for another eight to nine hours (except Sundays, where he works for another 6).

He tells me that three new supermarkets have opened in the last few years, unbothered, perhaps because the Yoons have watched them come and go over the years, including multiple supermarkets that have been bought out, then turned over again, often renamed each time. When I tell him about the tax benefits and other financial incentives offered to owners of supermarkets to open in the neighborhood he is somewhat bewildered, suggesting he was never extended the same benefits (including acronym-laden programs of the moment, like FRESH, see: https://edc.nyc/program/food-retail-expansion-support-health-fresh, which among other things, offers 25 years of tax abatement to supermarket owners). Harry also has a low opinion of what supermarkets sell compared to what he carries, if not the prices, then the quality of their produce (or, if all else fails, he could “get what they get,” implying he chooses not to). Unlike the supermarkets in the neighborhood, he explains, the workers at Yoon’s “manicure” the product: washing, cleaning, cutting the ends off (of lettuces, for example), repackaging, and “making specials.” In his eyes, supermarkets just “put it out.”

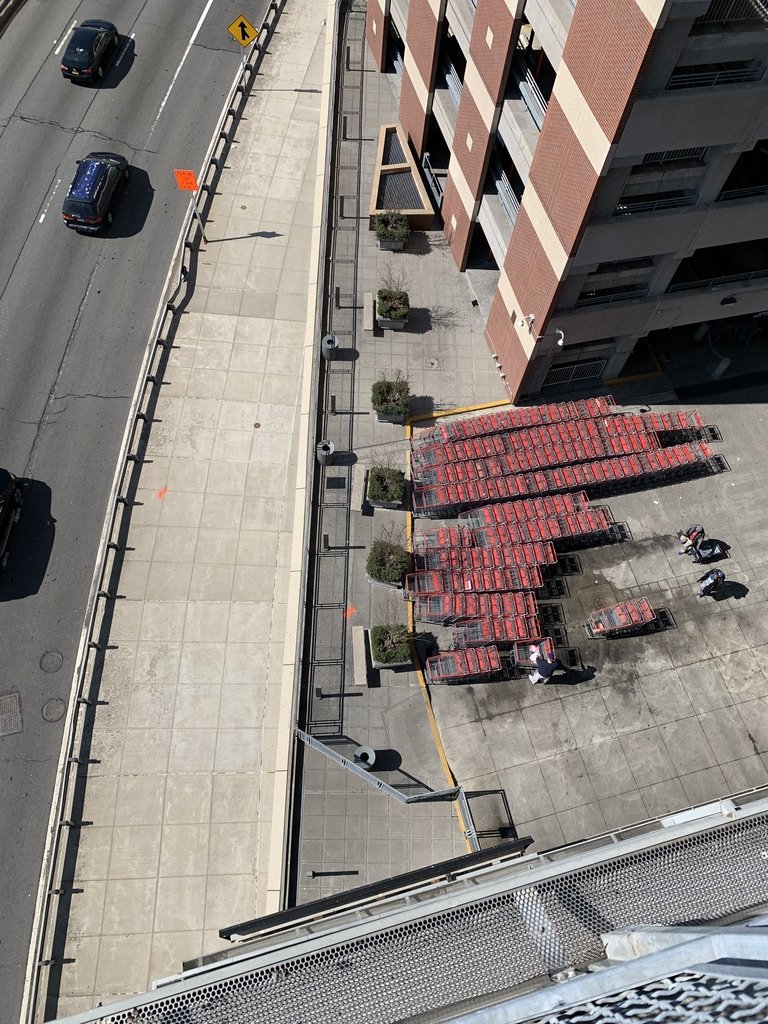

The “big box” stores, like those found in the East River Plaza mall near the FDR Drive and the East River, and the grocery delivery services, like Amazon and Fresh Direct and the 15-minute grocery delivery “micro-warehouses” all with delivery ranges (visible in-app) that cover the neighborhood, are, however, outside of what Harry considers his competition. Unlike the small grocers, street vendors, and most local supermarkets (via “last mile” distributors) who get their produce from Hunts Point, “big box” chains and platform-based grocery services bring it in by “the truckload.” They have dedicated supply chains which might even skip Hunts Point in the path from grower to distribution; and operate at economies of scale (at <3% margins; Deener, 2020; Lorr, 2021) that small markets could not sustain, by ways of direct relationships with growers and vertically-integrated (corporate-owned) or subcontracted supply chain management.

In the case of grocery delivery platforms, these corporations also manage the logistics of the last mile via platform-mediated delivery where workers ride e-bikes or cargo bikes, drive rentals or cargo vans from warehouses or other aggregation points to the final space of exchange (the apartment, home, etc). In other words, there are two levels of intermediaries that differentiate them from other small grocers like Yoon (supply-side and last mile). Talking about Amazon and other grocery delivery platforms, Harry explains “we can’t compete” with a gravity in his voice that is very much the same that I imagine taxi drivers might have had when talking about Uber in 2009—except he, like most food workers has no union, and unlike the capitalists operating at a larger scale (platforms, supermarket chains, or big box stores like Target) he has no industry association who can lobby or pay off politicians, or armies of lawyers writing policy that advantages him. There is a slow violence of global capitalism in the livelihoods of small-scale owners—of course, distinct from that faced directly by informal street vendors, or even that of the people who work in their shops. Platforms also change relationships downstream from markets: a clear example could be drawn from comparing the types of foods that Amazon/Whole Foods carries online and what is available at markets like Fresh Yoon, in relation to how the people of East Harlem cook and eat.

I will preface the discussion of customer interactions—the steady stream of four to five people, mostly women, in the store at all times that grows to six to ten after 5PM when people start shopping after they get home from work—with the generalization that relationships observed between the workers in Yoon Market and people shopping there are pleasant, cordial, brief—and regular. However, talking with Harry, the environment of competition and conflict expressed between the market and other types of produce vendors continues in customer relations. At every opportunity he tells me about how “customers complain about prices all day,” that they “want it ‘cheap.’” He often rehearses a response to a fictitious customer taking issue with his prices: “I’m not a fucking dollar store, alright?” (however, to be fair, this quote came directly after we were talking about “big box” stores, including Target and Costco, opening in the neighborhood and he was fired up). From Harry's perspective, prices start “at the grower,” at a distance beyond his control, while he has to deal with customers who prioritize—and shop at Fresh Yoon specifically for—deals (almost a ‘don’t shoot the messenger’ type scenario which he feels the customers don’t fully understand). He summarizes “customers, don’t have to buy [anything] I have to buy, just in case.”

However, what I have observed is more like negotiation than conflict, where customers reflect on what they paid in the past and see if there is a deal to be had. This negotiation process—also present in my observations of other street vendors—is the livilness of this space, a major distinction between what happens here and what does not in chains or supermarkets. This is about knowledge; for example, when a customer asks about the oranges: “Are these good for juice?” and the workers here can explain the qualities of the fruit; or talk about the spiciness of the chili peppers. In the supermarket knowledge of the product, including how to use it, is disembedded from the work of stocking the produce aisles (perhaps, existing in another form in a purchasing department). These interactions are, it must be pointed out, completely absent in platform-mediated exchanges of groceries. What types of knowledge, and their location in the commodity chain, in relation to the point of exchange, is a critical point of divergence for understanding and distinguishing different forms of vending operations; I would suggest, as a product of these day-to-day interactions.

There are, however, moments where other logics surface in our conversations; for example, Harry explains that his customers “want what we all want, the best quality at the lowest price.” This begs the larger question of whether conflicts are a result of the ‘free-market’ infrastructure of the food system, and if some other social formation could bring the different sides of these exchanges into alignment. And yet, conflict is ever present in the market, like in the streets where working people live; for example. almost every time I’ve visited, Harry—or sometimes a defender from among the customers—counters calls of “Chino!” with “no, Coreano.”

Value is, in the end, something that can be measured, negotiated and agreed upon, held and handed off at the point of exchange. This happens at the counter of Fresh Yoon, the final point of exchange in a global process. It is also something of a central strategy for this market, to sell food by the piece as opposed to by weight. To be clear, with the exception of a few foods that are sold wholesale by the piece—or the “count”— such as apples and melons, almost everything at Hunts Point is sold by the weight. When I asked Harry about this conversion, he explained that part of it is about simplification, to make the math easy (more transliteration than translation) and part of it is about making transactions quick. What he doesn’t say, but I observe and work out through talking fruit over the course of multiple visits, is that this negotiation of value allows him to adjust and adapt as the product changes by a factor of time and in unpredictable ways.

Harry gives an example: “Apples come in an 80-count case for $40. That means I need to sell them for $0.50 each.” I might sell those for “3 for 2” (.66 each, a 25% margin that is almost unheard of in produce sections of supermarkets). It is clear that while he would prefer to sell at that margin all the time, price is variable and changing. He often ends up selling fruit for lower prices, breaking even, or in some cases, cutting his losses. Where the beginning of a case might sell “3 for 2” the end of the case might sell “2 for 1” ($0.50, break even); he might even have to sell “3 for 1” (at a $-0.17 loss). There is one unshakeable rule at the bottom of this arc, Harry tells me, “anything that is a dollar sells, everytime” (makes you wonder if maybe he should qualify his statement, that he is not a “fucking dollar store” all the time). Unlike the supermarket, where valuation happens at the level of “truckload” or shipping container, Fresh Yoon operates case-to-case (which begs the questions: what is lost, or reinforced, in operations at different scales?)

Prices are set in a complex mathematics, with steady variables of past prices, knowledge of wholesale costs at HP, and his perception of what customers will buy. And then there are the unknown factors: “gas prices, shortages, weather, any number of things that change what I buy it for.” Sometimes the salespeople at Hunts Point tell him to expect price changes that never happen (“lettuce is going up, buy now”) not to mention that he can’t buy more produce than the store can move before it goes bad, regardless of wholesale prices (in ways that a larger scale operation might take advantage of). In addition, he never quite knows about the prices he pays at the wholesale market, explaining that vendors “tell you they got it for such and such a price, but you can’t ever know.” What is clear is that prices are difficult to forecast, which reinforces a logic of conversion and variable pricing.

The logistics of Yoon Market are about Harry getting in a van four or five times a week to travel to Hunts Point in the early hours of the morning. It is about managing relationships, not the least, between Harry and the worker who comes after him, post-negotiation, to pick up the orders from the wholesalers and deliver the cases of produce to the store. Logistics is also a question of material transformation: food decays, ripens, rots, peaks, as fruits and vegetables come in and out of season, transit, or cold storage. Logistics is about controlling the process in time: slowing down the decay of food in cold temperature and selectively pulling out to put on display. The people employed at Yoon Market work at a particular point of exchange in a longer process of controlling time by space, via temperature. After the worker drops off food from Hunts Point around 11AM, food is brought in by hand truck. “Anything that needs to go in the cooler, goes in.”

The “cold chain,” describes a central logistical feature of the contemporary commodity food system. It was designed specifically for meat products and meat-centric American diet adopted in the 20th century (Pilcher, 2017), as animals are dispatched, broken down, processed, transported, exchanged, etc; monitored via regulatory regimes and operationalized as protocol, for example the tracking mechanisms that monitor exchanges from warehouse to truck, or truck to truck, in the supply chain. This works in a similar way for managing fruits and vegetables, except that a range of temperatures are used, strategically, to control the process. It must be emphasized, temperature is about controlling a one way process, from unripe to rot.

Different vegetables are treated differently: yuca is coated in food grade wax at the point of harvest; storing some root vegetables or alliums in cold is counter-productive, as they begin to sprout or change textures; cilantro is shipped cold but unwashed to slow the breakdown; scallions are shipped covered in ice; basil, however, ‘dies’ quick in refrigeration. The logistical organization of exchanges of fruits and vegetables are often designed to manage the materiality of different products in transit (Deener, 2020). For example, contemporary mass-produced varieties of tomatoes are bred for characteristics that allow them to be picked green, and ripen consistently when treated with ethylene gas inside the shipping containers that move across highways or oceans.

These temperature-controlled chains extend in the backrooms of markets. Sometimes labor is organized, in the day’s tasks, to speed things up: “avocados come ‘hard as a rock,’ we let them sit in a warm place for a few days, then put them out.” The workers at Yoon’s monitor and rotate cases, according to the type of product, through space at different temperatures: cold, ambient, and warm (like the top of the walk-in refrigeration unit) to encourage ripening. They take inventory over the course of the day, communicating needs (“someone is working in front with berries today, he lets me know what’s running low”). Harry also monitors what is in stock and running low, what is selling, and collects this information on a clipboard he keeps at the counter behind the register, for use on the next trip to Hunts Point. He explains it via three columns in the sheet “how much do we have on hand? How much do we need? How much will we buy?”

At the organizational level, the materiality of fruits and vegetables is aligned with the management of relationships, via Harry’s mental map of seasons, prices, information from suppliers or customer interactions, modes of tracking inventory, and unit-level economics that guide decision making. It must be emphasized, again, that the process is one way street: it is linear. And yet, the process is also cyclical and complex—like metabolisms of the body sustained in a social process, cycles of harvest and seasonality, or the global circuits of capital which shape each—what is sold in the market is the product interactions often outside of the control of the people who work the point of exchange, beyond even the seasoned food worker’s knowledge of past interactions.

Harry tells me, “the produce business is about loss. You know you will throw away a certain percent.” It is also about knowing when to buy, and how long it will take to move something (before time takes hold). The strategy of breaking food down into pieces begins to make more sense when you view it this way. The bins outside on the avenue are filled with material objects in their twilight; the produce vendor negotiates time, in space. The community relies on their labor to suspend foods at the perfect moment—and they come to depend on deals after the point of decline. We must remember that the perfect pyramids of the produce aisles in the corporate supermarket, especially in wealthy areas, have very little to do with food being nutritious, delicious, or useful; it is worth mentioning, too, that people who order groceries via delivery services don't even see the product before buying online, instead purchasing fruits and vegetables by symbol or avatar. This is potentially another important point of divergence, based on use value.

The Caribbean women who shop at Yoon Market have recipes for platanos at every stage: from rigid green, to spotted yellow and brown, to black and soft. While food policy circles and venture capital delivery ‘start-ups’ with business models for selling ‘imperfect foods’ often present some variation of a moral argument for different types of consumption, there is another angle here: based in tradition, intuition, culture (and I would suggest, relationship to nature and the land) that the community brings to the market. This, too, is knowledge the vendor must account for, not simply in knowing the ethnic groups or clientele—the first level of this topic in my discussions with Harry—they also must know something about how people use foods, their traditions, their culture, in a sense, aligning the knowledge contained an operation, embodied in the work (which includes the logistical intricacies of interactions with infrastructure) with the knowledge built over generations, in places far, far, away.

Even as I am told by Harry that he does not take requests for what to carry, due to the economic limits of time (“you might want it, but will you buy the whole case?”) or of misalignment (when people asked for celery root, and when he brought in the “round ones,” the actual root as opposed to the stalks/leaves “and no one bought them”) the Yoon Market represents the accumulated knowledge of generations, built from interactions over time. This knowledge was inherited by Harry, as the product list was basically intact when he took over five years ago. While it is not possible to interview the generations who ran the store before him, his parents and aunt and uncle, you can imagine decades of exchanges that have shaped this market. It’s why he knows that people will come to “him” for sofrito, the flavor base of Spanish-influenced cuisines that is slowly cooked in oil at the beginning stages of many recipes, which shares the name and some of the technique with the cuisine of the colonizer, but in the Caribbean contains a different mix: of culantro, cilantro, ajicito peppers, and other ingredients (many families and cooks have their blend) in addition to the onions, garlic (and sometimes tomato, depending on the recipe) of traditional Spanish cooking. While the owners of supermarket chains and networks of operations that supply them actively shape consumer preferences, even creating new products based on hybrid varieties optimized for transit (Deener, 2020) it appears that this is a more multi-directional process in the small market.

The materiality of delicate, fresh herbs like culantro, that quickly melt away into brown, wet clumps, is a means to draw out another important strategy that sets this market apart: “we have the advantage vs. the supermarket, I can buy everyday” Harry exclaims, suggesting that supermarkets and “big box” stores get a shipment once, maybe twice, a week. When he tells me “we don’t overbuy” it also verbalizes a massive commitment in labor, one he makes personally, to the logistics that give Yoon’s the edge, if a slight one. Harry doesn’t cook with sofrito, but he knows what people look for (although, we must not be essentialists; he also tells me he hates ginger, which is difficult when “you are Asian”). He makes a living, not only from logistics, but from social relations—work and labor—in distant places.

Harry tells me about mangos: “in the [New York] spring, mangoes come into season, first in Mexico, then the Caribbean, then California.” In the cold months in New York, this process moves southwards crossing the latitudes of America opposite the equator (especially in places like Chile and Brazil). “Counter-seasonal” produce requires a complex process, across space and time which creates the regularity, availability, and stability of the supermarket produce aisle (Deener, 2020). Yet, in the small market, seasonal fruits enter the market in different ways. Soursop, or red and yellow dragonfruit (guanábana and pitaya in Puerto Rican Spanish) are only carried sometimes, even when you might find these “exotic” and “tropical” fruits in upscale markets like Whole Foods, “the prices I would have to charge” are too expensive for people in the neighborhood to buy. He gives me the example of passion fruit (parcha or maracuyá, depending on where you are from) Harry tells me “it’s not cheap, so I don’t have it now.” When I told him that a nearby street vendor had them for sale, he assured me they are tiny (without seeing them, correctly) and offered a defense: “tell me the price, I’ll tell you if you’re getting ripped off.”

Time is also a question of quality: time changes the textures, flavors, aromas of foods in ways that are measurable by distance. Harry, like many a cook, can tell the difference between fruit that travels for “a couple days vs. couple weeks.” In the short seasonal windows which bring prices down, working class communities in East Harlem cook and eat a bounty of global food for cheap. For the rest of the year, prices are up; they might have to make due with whatever joy remains in cold storage apples, oranges, and other varietals of mass-produced commodity produce; or the by-products of global “socio-technical” infrastructural regime organized around supermarkets (Deener, 2020) which means that wholesalers, at times, need to sell cheap and move their goods quick, making deals with vendors like Harry Yoon.

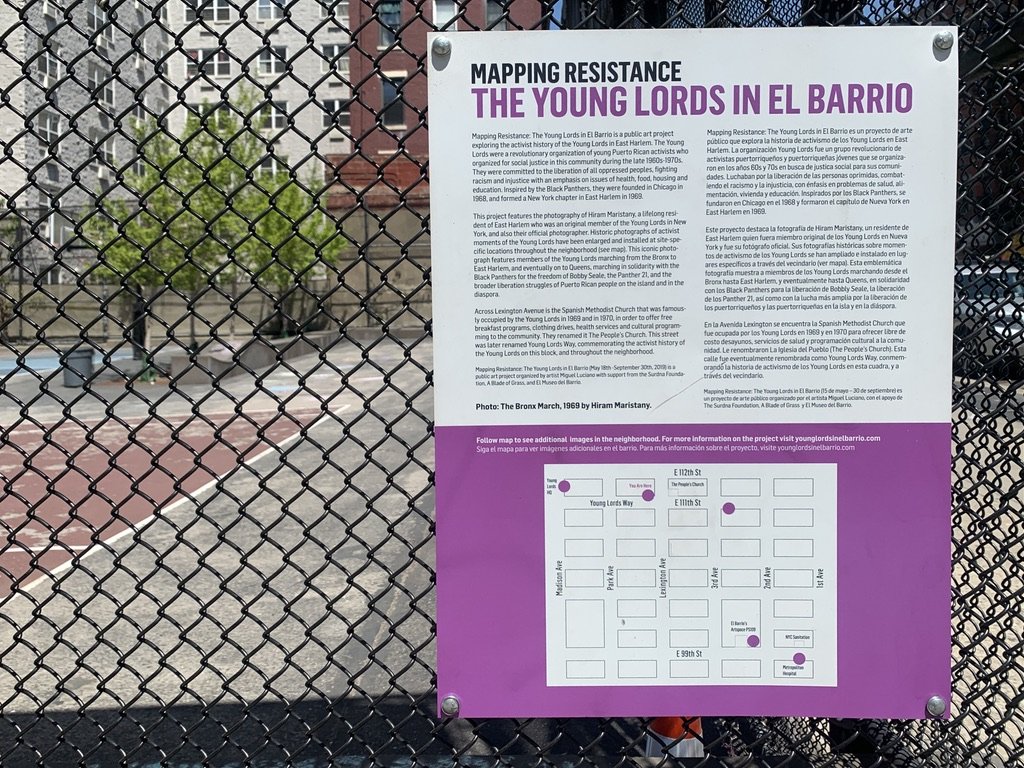

There are, however, other scales of time here that speak to deeper histories, beyond interactions of any single market, in the displays at Yoons. We can see this in the bins filled with tropical root vegetables at the back of the store: batata, yams, yautía, malanga, among many others. If we think about the historical process which shape the ways that people eat, and zoom in close enough on how they cook, we see something more profound in the negotiations of exchange. We could start with the names on display: written mostly in Puerto Rican Spanish. This speaks to the neighborhood, El Barrio, and especially the Puerto Rican influence in the 1970s when the Yoons took over the store, before patterns of migration from other spanish-speaking communities became more dominant. It is also about the geography and history of the Caribbean Atlantic in the 16th century.

Malanga (or yautía, taro in English) is an ancient cultivated crop from South Asia that was brought to Africa first via exchanges across the Indian Ocean and later to Americas during the slave trade; yuca (cassava, in English; the base ingredient in tapioca starch) moved the other direction to Asia via Europe. Borders disappear up close. This is particularly true with food, where nationalisms are easily undone even by the slightest historical attention. What remains, then, is something more important to deal with directly, including legacies of colonialism and slavery, and an economic system based around exploitation and dispossession, which require more nuance than discourse by proxy (“of things” instead of social relations). We also make space for the complex stories of the people whose work makes up the process of the food system on which we all rely, including the son of Korean immigrants, who works 362 days a year alongside the workers in the store he owns.

In examining the process of over space and time, via contingent relationships that sustain it, we can begin to resolve the linear relationships between links in a chain, with the cycles by which different organizational forms—and social formations—are reproduced over time, day-to-day and over longer historical trajectories. We can begin to ask new questions like “what are the “logistics” of feeding a family?” and include the work of mothers, caregivers, neighbors, families, groups organized around culture, tradition, and beyond. Consider the chains of spatial and social relations that play out on a global level, turning on perennial frontiers of fruit production, planting, ripening, harvesting, bound by time; on one hand: pushing outwards, north and south, from the equator as the earth rotates on its axis, on the other: in the chains of social relationships—and intermediaries between them—in a global social process of exchange, of which the food workers in shops like Yoon Market are last in a long line before food exits the commodity relation (and, literally, via the work that often goes unpaid and unmentioned, used to feed another commodity sold at the market: labor).

The work of vendors connects the networks of work across vast distances, at many scales, at the terminal end where hundreds of commodity chains come together, as work continues beyond the point of exchange, in provisioning, caring, feeding (etc), beginning with the journey home, often by hand cart or carrying bags on foot, en route to other social possibility by way of the kitchens of the city. Like is true in agriculture where most of the food the world eats is produced by small scale growers, most of whom are women (Shiva, 2016), where most of the meals eaten are produced in domestic kitchens, where production is also organized outside the wage in commercial spaces, the world gets their fruits and vegetables from sources outside the supermarket.

This research, even as it is ongoing, has started to bring into focus ways that we might find similar dynamics in the cities of wealthy countries like the United States, when you move beyond downtown out into the edges of the city. I might suggest that what we learn here might also allow us to move beyond working class neighborhoods to take a closer look at the center of the city, in business districts like downtown Manhattan. My thesis is: across the uneven and unequal geographies of global capitalism that feed the global city, we will find that people (poor, oppressed, marginalized, subaltern, undocemented, etc) have many ways of knowing, being, and doing they put into practice to make “ends meet,” and that you will find spaces organized around their needs, and ways, wherever they go. Small markets, bodegas, and street vending as institutions, cross geographic, socio-economic, cultural boundaries in the city. Exchanges in them suggest logics beyond the market and the state as central in the process by which the city cooks and eats; they also might suggest that the process of food systems organized on a global scale, between the peripheries of the south and the core of wealthy nations of the north might be more similar than different. What is clear, is that the “last mile” of this global process is a contested space that plays out in the streets, sidewalks, and ground floor of the city, between different forms of work and labor, sometimes cooperative, sometimes conflicting, always negotiated at the point of exchange.