Virtual Restaurants, Ghost Kitchens, Work and Heat: Delivery Platforms in the NYC Food System

Scroll for slides adapted from a presentation at the 2021 Eastern Sociological Society conference.

HOW ARE KITCHENS IN NYC REORGANIZED AROUND DELIVERY PLATFORMS?

HOW DOES A REORGANIZATION OF KITCHENS CHANGE THE SOCIAL PROCESS OF THE NYC FOOD SYSTEM?

“Ghost” kitchens? “Virtual” restaurants”?

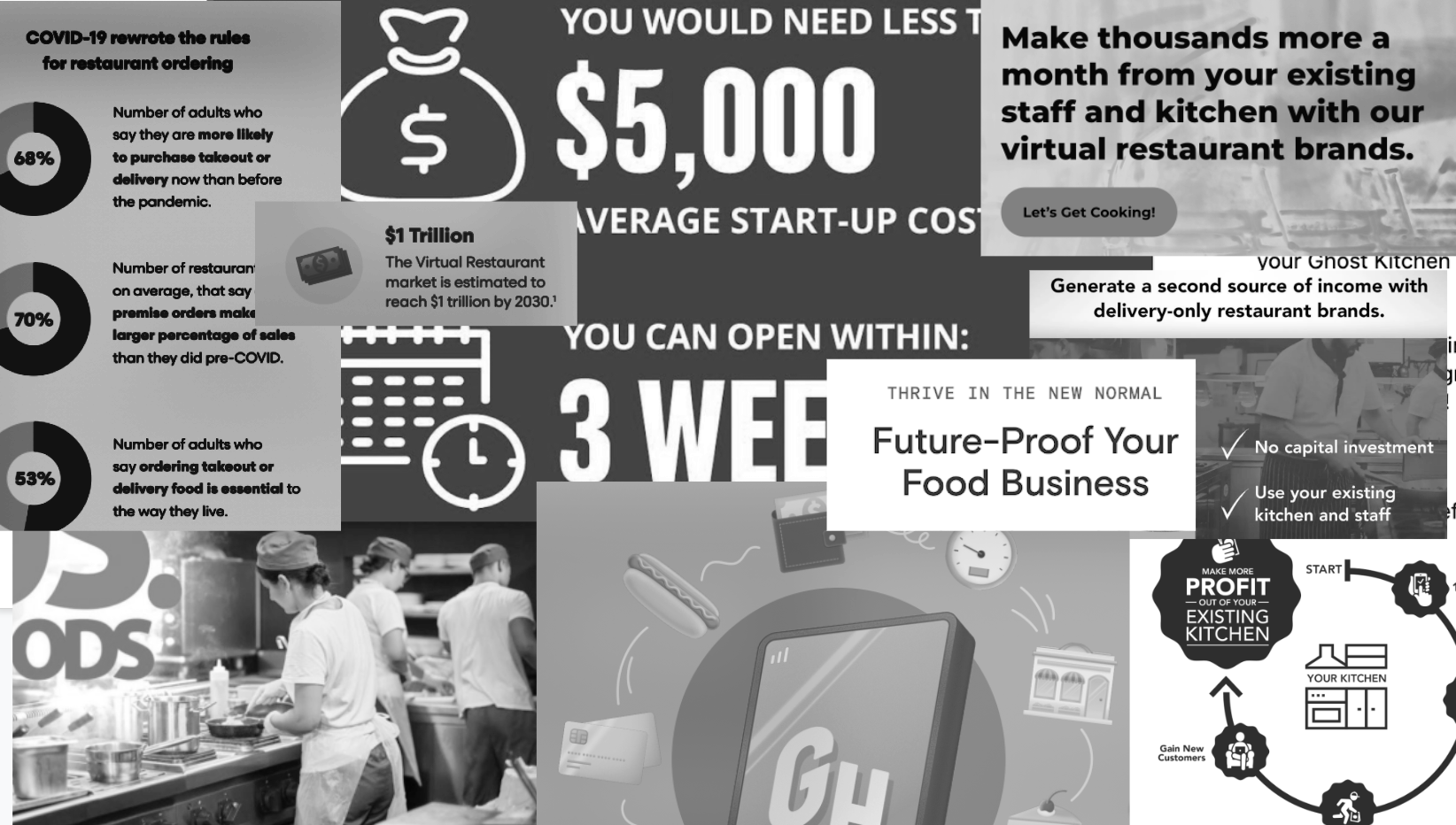

A ghost kitchen is a term used to describe a delivery-only or delivery-centric operation that produces ready-to-eat meals sold online through delivery platforms. This is the term most commonly used in the United States. In China and India, the world's first and second largest markets, respectively, for food delivery by sales (Statista, 2021) people tend to use the term “cloud kitchen,” while commentary in the UK is focused around “dark kitchens.” The term is applied to delivery-centric operations with limited forms of service. At the same time, it is applied to spaces where the FOH has been replaced entirely with platform-mediated delivery workers. As this study will show, both involve the externalization of parts of the process of kitchens upstream in commodity chains, the creation of new roles, and new spatial and temporal divisions of labor.

A related idea is a virtual restaurant (VR). This refers to an online-only menu that appear on delivery platforms as a “restaurant” or a brand—independent of the name of the operation that produces the food. For example, a diner in brooklyn that sells food under 18 different names online (Fortney, 2022). Adding to the confusion, the idea of a VR is sometimes used interchangeably with “ghost” (cloud, dark, etc) kitchens. More than a symbolic act, digital rebranding, marketing trick, or workaround to regulations or health codes—although a VR may also be one or more of these things in different cases—these models also represent a material and symbolic, digital and spatial reorganization of the process of kitchens. Like ghost kitchens, we can understand these changes in the organization of space, time, and process in the “host” kitchens (as some companies that sell VRs have tried to brand this relationship).

This study advances what I will argue is a more useful term, platform kitchens: kitchens organized or reorganized around digital exchanges on food delivery platforms. This broad definition lets us capture the spectrum of changes inside existing operations, primarily in restaurants, but also hotels, supermarkets, and retail spaces. It also lets us capture new organizational forms structured around, and contingent upon, platform-mediated delivery. This study will identify six types of platform kitchens, however, I will start here with the characteristics that each share, in degrees:

1. contingency in platform technology and platform data in the labor process

2. they swap “front of house” service roles (typically those paid in tips) for the labor of delivery workers (‘in-house’ employees or independent contractors working gigs on delivery platforms)

3. the “back of house” spaces of production for exchange in these models represents a significant reorganization of the workplace, the work day, and the work in kitchens.

Some examples in NYC:

A bodega in Brooklyn that sells food from 6 virtual restaurants (brands that appear as restaurants on delivery platforms) alongside standard corner store food (sandwiches, halal chicken over rice, etc).

A bakery in East Harlem, that reheats and resells proprietary, licensed frozen dumplings.

A parking lot under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, that hosts a mobile delivery-only kitchen (that looks like, but isn’t a food truck).

A delivery-optimized — and delivery platform partnered — rental kitchen that hosts multiple delivery-focused operations (alongside other types of food businesses, including caterers, meal prep, producers of packaged foods) inside the former commissary space of another failed delivery ‘start up.’

A fried chicken fast food restaurant in the Bronx that sells food from celebrity-branded VRs (cookies for delivery named after R&B singers, rapper-fronted chicken wings, meals with pictures of Food Network personalities on the packaging, among others).

A fine-dining trained chef whose delivery and pick-up only “pop up” has moved around the city, who takes pains to deliver high quality food but due to platform fees often has to make hard choices (example: between eco packaging or raising prices).

A Chinatown, health-focused, bento box “fast-casual” restaurant that did about 75% of sales via delivery platforms, then closed (according the former chef) because of platform economics (where high fees require increasingly unsustainable high volume, low margin exchanges).

A "virtual food hall" in midtown with 14 delivery concepts (from VRs to delivery expansions from existing NYC ‘independent’ restaurants to delivery from fast food chain restaurants).

A converted warehouse space in Queens that functions as delivery site, a centralized production commissary for multiple other satellite “ghost” kitchens, and is also an Amazon logistics hub

METHODS:

HEAT = (A % OF LABOR IN SPACE + TIME)

Temperature: used to coordinate/control the process. Examples: delivery ranges and delivery windows, HACCP protocols, DOH regulations, recipes.

Following the organization of work in a kitchen, heat is a means to:

locate a space in a social process

map the work in a kitchen to work in other spaces—via observable relationships, what is visible online

describe a process organized across multiple kitchens

PLATFORMS CHANGE THE WORK DAY

“Cook’s time” (Fine, 1996. 54) on delivery platforms:

Rhythm: platforms mediate exchanges

Tempo: set via delivery app, algorithm, geo-location

Synchronicity: platforms align (primary, secondary, tertiary) temporal cycles (production, service, delivery)

Duration: algorithmic management (what is in/visible on platform U/I?)

Sequence: cooking by protocol, in-app feedback, organized around new roles (“operations” teams, logistics, R&D, remote management)

One observation: new time conflicts! (vs BOH/FOH tension in traditional restaurant)

Kitchen rushes to [accept] every incoming order on app because the economics of platforms require that they produce up to 30% more food to make the same money; cooks push out delivery orders as fast as possible.

Delivery workers who are paid piece rate (and get bonuses for meeting a daily order completed milestones) mark [received order] in-app upon arrival—before they have the order in hand—so they can receive their next order. If kitchen is behind or messes up order, this creates major problems (and both kitchen and delivery workers might receive negative reviews, which affect the possibilities for future orders/work).

If we want to know why delivery workers in the city do not stop at red lights, we should look at how platforms structure the process.

PLATFORMS CHANGE THE WORKPLACE

The street is a workplace.

From tipped “service” roles to gig work.

LIMITS OF SPACE: 2-3 workers, 200-300 square feet!

Limits to equipment, space, storage.

Traditional restaurant operations work within physical limits of a dining room (and theoretically, set geographic, social, and cultural limits of customers). Apps connect kitchen to tens of thousands—same peak times! (lunch/dinner “rush”).

Ghost kitchens (and VR concepts) require other kitchens: operations often extend outwards through complex production processes upstream in commodity chains, in other kitchens.

PLATFORMS CHANGE THE WORK (PROCESS AND PRODUCT)

A reorganization of kitchens around new geographies of “remote” and “hybrid” work.

Kitchens: from a process organized on “three sides” (Whyte, 1949) to four (or five) sides (all visible online and in-app, except the “black box” of data platforms extract).

Cooking data: the entire process is organized around generating data aggregated and later sold by platforms.

Automation: not ghosts, not machines. A “re-division” of labor around technology. Reworking of knowledge and skill, roles. If there is a “ghost,” it’s the chef.

Downwards pressure on “independent” owners (fee structures, advantages high volume/large-scale industrial operations—fast food restaurants are undisputed beneficiary of new models)

Platforms charge between 15-30% in fees to restaurants (some VR agreements bring that # to 45%). This changes the political economy of approximation:

Standard “kitchen math” = 30:30:30 (overhead:goods:labor) on revenue estimates (for food with temporal limits, meaning it decays).

“COGS” + complexity + process = 2-5% profit margin. This, however, is a best case scenario, restaurants almost never make 5% profit.

Q: Where does an operation find money to pay for 15-45% fees?

A: Through surplus value created by the labor of food workers! (Pitches to owners of restaurants often go something like: ‘use you existing space and staff to maximize revenue.’)